|

Memory Lies in Dreamland My memory lies in Dreamland. Not that all my memories are phantom, but the most potent remembering I have experienced was at a fun fair in Margate. I remember little, especially of my childhood, but, a couple of years ago, standing in Dreamland before the wooden roller coaster of which I was terrified as a child, I was overcome with a physical sensation, returning me to my childhood with such vivid immediacy, I thought I might start shrinking. Words were locked inside a somatic experience. The leg weakening excitement and dread of the four year old me coursed through my body. Collapsing, onto the ground or back inside myself, were intoxicating possibilities. This felt like living inside a memory rather than recalling or redrafting it. Testing times For the past year as the pandemic has writhed and retreated and writhed again, I have been meeting with M once a week. We - him, my eighty three year old father-in-law, and me, with a life long interest in ageing - explore the ideas, feelings and experiences around getting old, memory loss and how to spend the declining years as gracefully or, perhaps more importantly, as fully as possible. The enforced isolation of Covid has ravaged the lives of many of the elderly, and M is no exception to that. M comes alive in the company of others and, for most of the last two years, no company has been had. A conversationalist, his tongue has been stilled, and with it something essential to his existence lost. My mother, in her late seventies, was living alone in another country in which she does not speak the language when lockdown was enforced. She was untethered from her routine: her daily lunches in a local restaurant and the regular gathering of friends in a bar in the early evening. Silence descended on her life. And, with that silence, a retreat into an internal space unattached to others, to concrete ideas, to time. Growing old and covid: a disastrous cocktail to wrench hands from a hold on life. Simone de Beauvoir in The Coming Of Age, her fascinating philosophical exploration of ageing, and its resonances for individuals and the societies we construct, argues There is only one solution if old age is not to be an absurd parody of our former life and that is to go on pursuing ends that give our existence a meaning - devotion to individuals, to groups or to causes, social, political, intellectual or creative work. Isolation enforced, despite the supposed connectivity of the digital world - a world my mother has never set foot in -, is a sure fire way to sever ties, to unmoor meaning. To paraphrase Sherry Turkle, Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology at MIT, being alone together is a poor substitute for being together. Alongside this, there is the battle against tiredness, the shrinking motivation, the sloth that an ageing body can induce. As Voltaire wrote almost three hundred years ago, The heart does not grow old, but it is sad to dwell among ruins. What else can a sad heart do but follow the body into decline? Unfortunately, these ruins are not readily visited or attended to by those who clamber over the Acropolis or the Colosseum. For a society that champions youth and independence, these ruins are, at best, hidden away, or if they are out on the streets, in cafes, restaurants or bars, they are rendered invisible. Simone de Beauvoir Memory falters with the body. The slippage of short term memory, threatening the bulwark of long term memory, is fought against, or strategies are manufactured to bypass the forgetting. A forgetting captured in Billy Collins brilliant, plaintive poem Forgetfulness , which begins with the early disappearing nouns: The name of the author is the first to go followed obediently by the title, the plot, the heartbreaking conclusion, the entire novel which suddenly becomes one you have never read, never even heard of, and continues to Whatever it is you are struggling to remember, it is not poised on the tip of your tongue or even lurking in some obscure corner of your spleen. It has floated away down a dark mythological river whose name begins with an L as far as you can recall M and I continue to take our weekly stroll on the banks of Lethe, talking as the water splashes over his shoes. My mother has begun to paddle in its shallows. Her hands hold the rushes that line its side. I try to lift her attention from the waters racing beneath her with questions, attentiveness, love, to keep her at the river’s edge. But, as My Mother Weeps below reveals, the waters are rising. A necessary companion Before Covid compounded the isolation and loneliness of the elderly in society, that of M, my mother and many, many more, I read Nicci Gerrard’s profoundly beautiful, and inspiring, What Dementia Teaches Us About Love. At the core of the book, alongside other heartrending stories, is her father’s ten year struggle with memory loss, his loosening of self and the damage done by negligent care. Tears may fall, but Gerrard's determination to bestow dignity and love on those that can no longer bestow it upon themselves is rousing. The book is a necessary companion, a boon for anyone journeying into the uncertain terrain of a loved one being plunged into forgetfulness. For Gerrard, and the throng of dedicated people she meets working with those shredded by dementia, Validation is crucial along with a patient determination to find (and hold on to) the unique and precious person who may be obscured by their dementia. Both Gerrard and De Beauvoir write about how their societies treat the old, and neither France in 1970, or Britain in 2019, come across as places you would want to grow old in. What both advocate, in their very different ways, is a reframing of how we view, care for, accept and celebrate being old. A place most of us will get to without heeding how we treat those already there. Gerrard, visiting a ward, watches a fleshless, frail, elderly woman "immmobile... only her bony hands fluttering." At her bedside is a framed photograph of her as a young woman on a beach, paddling. holding hands with a young man and smiling. What Gerrard comes to, is that within this ailing frame the young woman, seemingly buried, is alive. Our histories are contained within us, and whether we can recall them or not, or others can reach to them through touch, song or a favourite food, we should be treated in a dignified way that celebrates all that we have been. This hopeful, smiling woman in the photograph is the same woman who lies unattended in her bed. She may not be able to recall, or redraft that memory, but it is living inside her. She "housed both the old and young self and everything in between." Sign of the Times

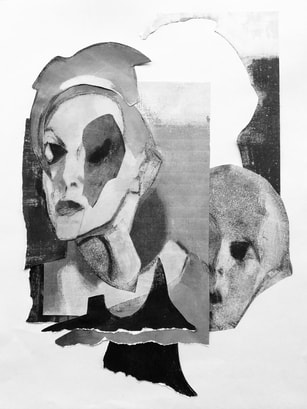

My mother weeps My mother weeps My mother weeps like a small child. Her shoulders shake. One hand rests on her face covering one crying eye. It shields half her forehead, a cheek, half her mouth, lips and chin. It is a strange image, and, as I hold the other hand and offer reassurance, I am struck by its unnaturalness. The hand, the half face, the weeping. My mother weeps. My mother never weeps. Her weeping now is not my mother’s weeping. My mother is not my mother. My mother weeps. I cannot remember the last time I saw her cry. She has not cried for at least thirty years. She sits in an armchair in our living room and sobs. This is a deep, momentous and fearful outpouring. Her body convulses, the words she is trying to get out are swallowed. Gasps for air, the only accompaniment. My mother weeps My mother weeps. She has lost who she is. A woman who never weeps and this weeping does not belong to her. It belongs to a woman who cannot remember why she is here, where she lives, or what has been happening to her. The unknowing of all has brought tears. These tears will not stop because they cannot be pulled in to a history. There is no drying comfort of "It will be all right". The "It" has been severed from the continuous thread. My mother weeps My mother weeps and I have to hold back my own tears. She is the frightened child that I once was. The confusion and the despair and the terror shakes her whole body. Steeling myself, so that I am not taken by the waves, I comfort her, tell her that I will take care of her, that she is surrounded by people who love her. Through her tears she manages, Don’t put me in a home. Please don’t put me in a home. My mother weeps Simon Parker

3 Comments

JOAN WITHINGTON

1/1/2022 12:00:27 pm

Very powerful, sensitive piece of writing. You show a deep understanding of some of the sadness and fear that accompanies the journey into old age.

Reply

Helen Greaves

1/4/2022 11:57:21 am

I love this poem Simon. It's very moving. I think memory is contained in our bodies perhaps more accurately than in our heads. Your experience in Margate seems to bear that out. As for ageing. I lost my uncle last June at 89yrs and spoke to him hours before he died. He was mentally unchanged to the end, sharp, witty, observant with a clear perspective. That experience taught me a lot. Unless we are unlucky enough to meet dementia, we are ourselves to the end. And then we're gone. I found it heartening and real. But dementia is another story of course and family and friends experience the slipping away and agony of losing the person before they are gone. All food for thought. But what would life be without death? Unbearable I think.

Reply

Billy Ridgers

1/6/2022 01:16:35 pm

What's happening? This is awful.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Writing into the dark Read More...

May 2024

Categories |