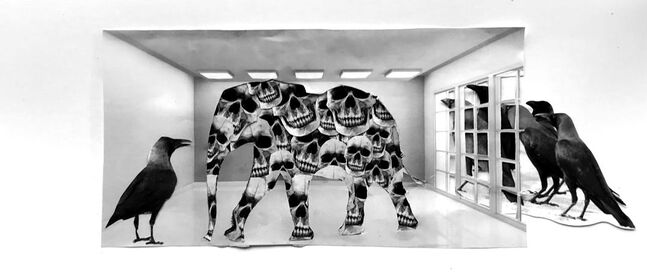

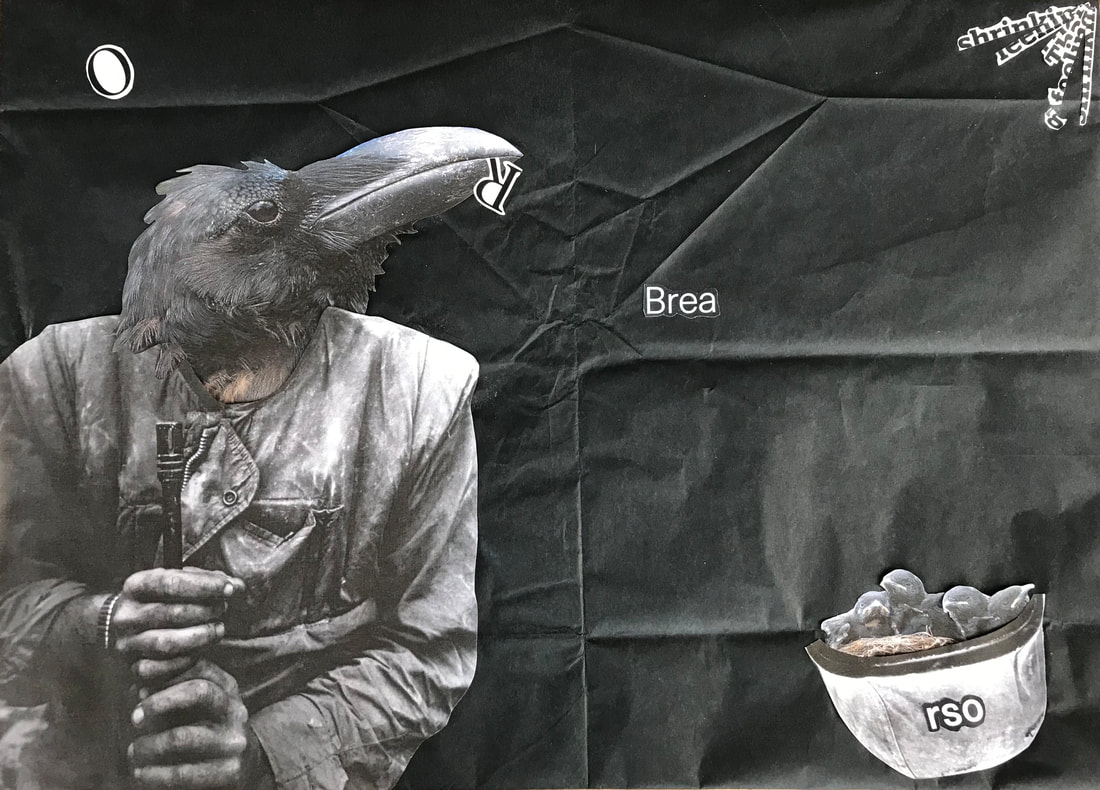

The Elephant in the Room (Simon Parker)  What we talk about when we talk about death... Death usually ushers us out of the world but with me he started early, accompanying me into it. He will, of course, be beckoning me at the end, pulling me slowly and painfully, or hurling me into darkness, but he is so familiar that I won’t be scrabbling to get away. I was born dead, unable to breathe, and put on a ventilator. Eight and half minutes later, medical intervention had given my lungs enough of a rehearsal that I was able to start taking on the job myself. I have always, sometimes jokingly, sometimes as explanation, offered this episode as the beginning that led me to become death’s familiar. I have always thought about death, read about it, pictured my own dying, and I continue to read and write about how we die, and what it might mean for living. The daily death toll that has dominated the media landscape has thrown this shadowy figure centre stage, a blazing spotlight revealing what was always there but carefully hidden away. The gruesome fascination with counting how many have died in tragedies around the world often seals away, like a trees protective healing after a leaf has dropped, any intimate letting in of death. Covid 19 with its rapacious scything and its blazoning across the news has broken the seal. The leaves of trees have suffered heat stress. As we moved through the twentieth century and set out into the 21st, death has been shepherded away from the public eye. As Atul Gawande notes, in his beautifully humane book, Being Mortal, in the 1940s over eighty percent of people died at home, by the 1980s just seventeen percent did. Coronavirus may not have returned dying to the domestic setting, but it has brought death’s shadow to all of our doors. In a Position Paper published in The Lancet , Psychiatry, one of the authors, Prof Rory O’Connor, writes, ”Increased social isolation, loneliness, health anxiety, stress and an economic downturn are a perfect storm to harm people's mental health and wellbeing,”. This distressing and damaging consequence has wreaked havoc on people’s lives and torn at the already frayed seams of the mental health infrastructure. What hasn’t been included in the assessment though, is the clarion call of mortality. How the brazen, public appearance of death, has drawn our gaze. We live in sanitised times. We deny death’s dominion. But as political philosopher John Gray argues in Straw Dogs, his corruscating critique of American styled liberalism, despite the veneer and polish of civilisation we are still “animals” over which death will always have dominion. What we have become masters of, especially with the elevating of the individual as product, is tidying death away. With the current pandemic the mess keeps spilling back out. Scrabbling towards the end (Simon Parker) Back in 2015, as my father lay on his death bed at my sister’s home, I tried to talk to him about dying. I hoped that by talking he may feel less alone, that by sharing some of the fears and anxieties, the thoughts and feelings circling in his head, he would go gently into “the dying of the light”. He, as he had always done in my lifetime, wouldn’t communicate and the subject was only approached through humour. Humour had protected him in life, and it would serve him in death. What I felt, more about his life than his death, was that that humour, an understandable reflex against the pain of the past, stopped him living. Mark Twain argued that The fear of death follows from the fear of life. A man who lives fully is prepared to die at any time. The last thing my father said was a joke. He pretended that the nurse who was putting a needle into his arm for morphine had hurt him. Something along the lines of, It’s not enough that I’m dying, you want to beat me up as well. When the undertakers arrived to take his body away, they slid the pillow from beneath his head which stayed exactly where it was. I marvelled at this empty space, this vacuum between his neck and head and the mattress. He was gone. Death, its rigour, held this gravity defying place. There was nothing that we had said to each other to fill it. Reading and writing are a way of life, not, as some would argue, a retreat from it. I wrote about my father’s dying, and I spent the months after reading books about death and how we approach our end. This wasn’t running away from the grief but a way of wandering through it. I read, I cried, I thought, I questioned. I wrote a play, Aching Parts, about how we die. Most days I think about death, about dying, not in a morose and fearful way but instinctively. Now, death is everywhere and everyone is thinking about it. Or are they? There is a scramble to return to things as they were. For schools to reopen, for people to return to work, to the gym, for people to escape the isolation and strangeness that the pandemic has brought, for death to be tidied away once again. This feels like a missed opportunity. Economic worry, which carries education in its wake, is fuelling ideas about the future. With death having come so close to all of us, with our mortality so baldly exposed, is this what we want for the one short life we live. Death awaits so why don’t we start living as we really want to. Aren’t these the conversations, the desires, that should be driving us beyond an unchanged return. Pushing us to the life worth living, its energy increased by an acceptance of the inescapable end. Death should be kept from its hiding place. The tireless and brilliant Maria Popova has shown how other countries sensitively place death centre stage in children’s books, starting the conversation early, with death a protagonist in many wonderful tales. These stories characterise, and normalise, death for young children, and, I believe, make their lives much richer for it. Two of the books that Popova introduced me to, I use when teaching both adults and children, and often, in the many conversations I have about death. In Wolf Erlbruck’s Duck, Death and Tulip and Glenn Ringtved’s and illustrator Charlotte Pardi’s, Cry Heart But Never Break, there is an uplifting tenderness and truth about how it all ends. Erlbruck’s Duck, who has failed to noticed that Death has been following her all of her life, suddenly realises he is there. They spend time together, becoming friends. Duck suggests they go to the pond but the water proves too cold for Death, and Duck has to keep him warm throughout the night, her neck and wing laying across his sleeping body. Death is moved as nobody had ever offered such intimacies. This heartbreaking moment of communion and togetherness cannot prevent Death from doing his job. Ringtved and Pardi, delicately tread the same path. Death has come to a house to collect an elderly woman who is sick. So that he doesn’t frighten her grandchildren he leaves his scythe outside, resting it gently next to the front door. The children, to prevent Death going upstairs to their grandmother, keep pouring him tea and telling him stories. When Death can take no more tea, he tells these anxious children a story of his own, a story that strikes the same bell in Keats’ “temple of Delight” where “Veil'd Melancholy has her sovran shrine”. After listening, the children relent, accepting that you cannot have life without death. They let their grandmother go. Inevitably, we must follow out grandmothers and grandfathers, our fathers and mothers, but don’t we want to follow them knowing we have lived a life without fear. Until death is part of the conversation that may never happen. Erlbruck’s Duck and Death

3 Comments

|

Writing into the dark Read More...

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly