|

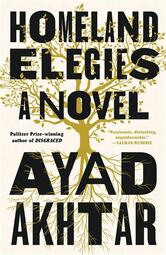

Broken Again My brother was most certain when he was most mad. Wrapped only in a thin, orange patterned sarong, he would leave our house, turn left and walk the fifteen yards into the three lanes of traffic on the A4 westbound. Cars hurtling along at forty miles an hour were no danger to him. The horn blasts and braking, swerving and swearing were all part of the plan. He was in control. Those of us who didn’t believe him were the fools, myopic unbelievers, drone like doubters; we hadn’t been gifted with the knowledge that he had: the third eye. In his digging down into the depths of his psyche, the human self - flimsy, fragile, loveable - had collapsed. Doubt had been banished and certainty was king. I wished it were true: rather than tremble and weep as I tried to coax him out of the road, I could have enjoyed his dance with two thousand kilos of metal and fuel. The psychoanalyst Darian Leader, in his humane, insightful book What is Madness, writes: The absence of doubt is the single clearest indicator of psychosis. One of the “everyday torments of the neurotic” is doubt. He offers numerous examples of the certainty laying the path to psychosis: A woman who knew that her doctor loved her when one day she felt a pain in her arm while doing housework: he must have sent her this pain so that she would return to see him. We may laugh at such magical thinking but those holding such certainties are, perhaps, in their deeper reaches, often perplexed, frightened, trying to make some significant and comprehensible sense of the world that places them at its centre. Spending time with my brother when he was at his most convinced, I was aware of a terrible fragility within him. Initially I was seduced by his certainty, like most neurotics , as Leader says: drawn towards someone who knows exactly what they want, who insists on some knowledge or truth with blind determination. Doubt gravitates towards certainty. Once I’d regained my imbalance, I felt that my brother’s delusional certainty was a powerfully constructed, impenetrable wall that was holding back all that would make him disintegrate, but I wasn’t sure. Ayad Akhtar in his beautifully riled Homeland Elegies, which I read last week, celebrates complexity, uncertainty, ambiguity. The book topples traditional boundaries, slipping between novel, essay, memoir and state of the nation exploration. When asked about how much of him, the Ayad Akhtar in the novel, is in his work: Did he, like the character in his Pulitzer Prize winning play Disgraced, think America got what it deserved when the twin towers were attacked? He muddies the freighted question. Born in America as a child of Pakistani parents, people clamour for Akhtar to make his opinion clear. Having heard Trump and his contentious statement in 2015 that he’d seen Muslim’s celebrating in Jersey City, Akhtar gives only what he can: The sentiments expressed in the play had of course come from somewhere, but how to express the complex, often contradictory alchemy at work in translating experience into art? The only thing I could put simply was that there was no simple way to put it. Putting it simply: words fail me. They often do. When I sit down to write doubt often pulls up a chair beside me. He sits there, small, pinched eyes, thin lips twisted into mocking grin, watching my fingers tap at the keyboard. Sometimes, it’s the familiar fraught relationship that an artist has with their material: you have an idea, a vision, a hope and scrabble to bring that into shape. You dig for words, change them, nestle one next to another, change a word, put a comma in, take it out and repeat and repeat and repeat; or you have a hunch you are getting close to what it is you are after, the inexpressible thrumming on the edge of expression; or in more prosaic terms: something that might stand up to your own self scrutiny, some measuring of what you have built that passes for good enough. Emigrants Sometimes doubt rides in as you read the crafted lines of another, their words shaped into something truly wonderful. Can your hands, heart and mind turn them with such gracefulness? Awed. Overwhelmed. Fertile ground for doubt’s flourishing. Reading Akhtar’s extraordinarily eloquent Overture to America which opens his powerful novel, I know there is a lot of work to do. Then there's the world. Always unstable, uncertain, but there are times when it is more nakedly so. The turbulence of today - war, the future of the planet, political impunity and the consequent apathy, viruses, - is raw, brutal, bewildering. Our human frailty exposed, it's easy to go scrabbling for certainties. Fear making us forceful in our beliefs. At the end of Homeland Elegies Akhtar writes Free Speech: A Coda. He reveals how when he was invited to speak at a liberal arts college in Iowa, he was deemed 'an "unsafe" presence on the campus.' Despite not having read him, no doubt in their mind, many in the college thought he should not be allowed to communicate. The woman who invited him Mary Marconi, a former teacher of his, had travelled through her own despair when students had refused to read certain writers' work because of beliefs held. Fortunately, she moved beyond her enervating gloom to a compassionate understanding of how their rigidity rose from a foundation of fear. Abandoned So what to do with all this doubt and uncertainty? Doubt paralyses, but it can also make you playful. If nothing is certain and you don’t know where you’re going you might test the water, seek out some hidden pleasure. Doubt leads into unexpected crannies. From a recent doubting, in which I was fretting and fumbling with the material and the matter of the world, I went playing: fashioning the words of others - some of my favourite poets - into a poem of my own. An A-Z. The form, a cento, meaning patchwork, is a collage. You may doubt it's mine, but here it is... unfolding a cento At the empty windows set in the tall house where fear leaps up inside me bathed in such unkindly light my body’ a sack of bones, broken within unfaithfulness no longer hurts in the lull before monsoon or typhoon but like bright light through the bare tree is a portmanteau of scream & babble or scrap and here I am turning your trophies to scrap at an illicit viewing but you do not have to forget mourning and mirth are two extended wings teetering on walkways that disappear I have given up all hope for what was whole the vacuous garment that limps at my heels as I go like a medieval painting’s kindling and with so much carrion in this graveyard for the sharp bones of my memory to turn my teeth to knives made out of soot, soup out of rust and, we try to understand things, each in our own way as an alchemist knows how to win your sixty trillion cells, all drunk with the live substance of a kiss polished and repolished by the hands of strangers they are frozen when there is nobody on earth who hears nothing — you heard nothing. [An A-Z through poetry. Sources in order of lines : Lot’s Wife, Anna Akhmatova/ A monologue of Prince Myshkin to the Ballet Pantomime of The Idiot, Ingeborg Bachman / The Fish, Billy Collins / His Picture, Elegie V, John Donne / No, never have I felt so tired, Sergei Esenin) / International Bridge Playing Women, Mark Ford / Vespers, Louise Glück / I’d played silence but later realised my word, Terence Hayes / Past caring, Mick Imlah / But you do not have to forget, Juan Ramón Jiménez /Lament 9, Jan Kochanowski / The Duckboards, Michael Longley / Migraine, Sinéad Morrisey / Whoever intends me harm, Pablo Neruda / The Haircut, Sharon Olds / A Musical Hell, Alejandra Pizarnik / ode to new money, Noel Quiñones / Daydreaming in the midst of spring labours, Aleksander Ristovic / The Silence of Plants, Wisława Szymborska / Wherever you are I can reach you, Marina Tsvetaeva / A drunkard, Ko Un / The Footsteps, Paul Valéry / The Divided Child, Derek Walcott / Empty Chairs, Liu Xia / A Father’s Ear, Yevgeny Yevtushenko / Siren and Signal, Louis Zukofsky]

2 Comments

|

Writing into the dark Read More...

May 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly