|

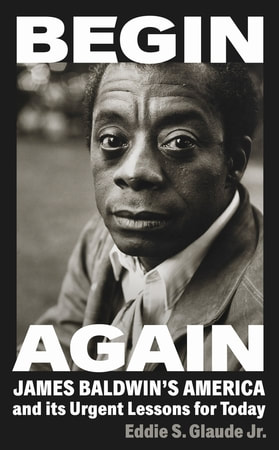

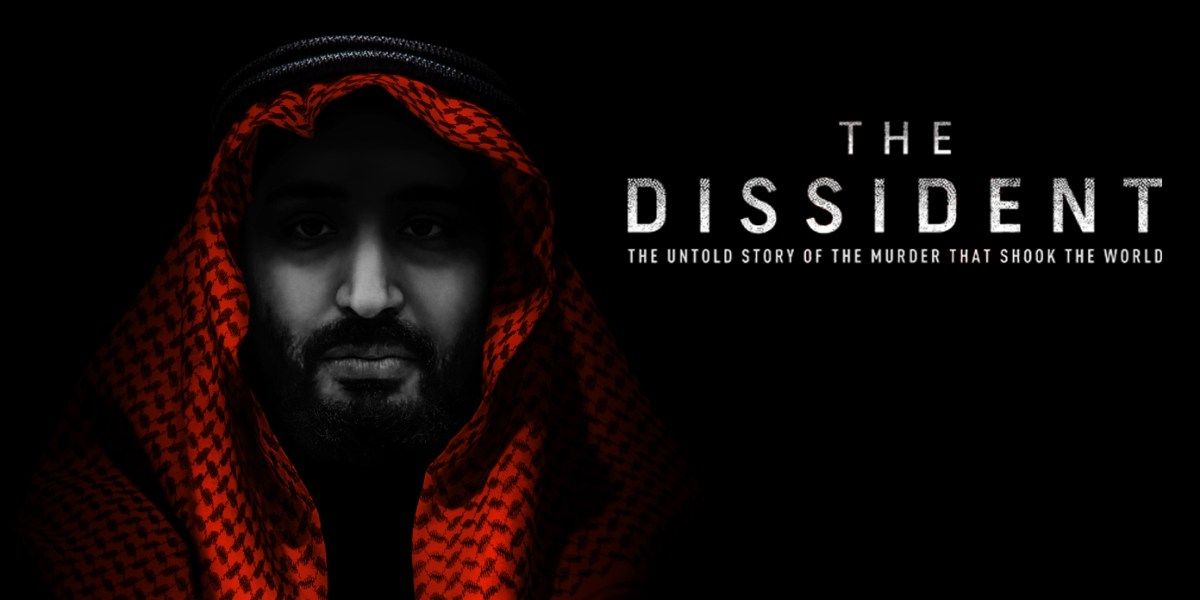

Eye-book (Rachel Clare) “Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.” Ursula K. Le Guin Words matter. The words we choose - we do have a choice - to use and the way that we organise them says so much about who we are, who we want to be and our hopes for the world that we live in. Writers - journalists and artists - work with words, they know that words matter. Politicians use a lot of words but rarely are they handled as precious materials. Words that may have been used in rhetorical flourishes to garner votes are forgotten, redacted, or hoist into shiny new configurations to ‘clarify’ what was really meant. This week the power of words, their consequences and their failings, have been strung out before me as I’ve stumbled from Baldwin to Biden to Khashoggi Last weekend, I took a walk through the recently published Begin Again with Eddie S. Glaude JR, who takes James Baldwin as poet guide to find his way to hope amidst the rubble of American democracy and race relations. This wonderful exploration of the failings of the United States and beyond sees Glaude navigate a troubled America: an America that repeats itself, an America that seems incapable of learning, an America that has been stolen. His pockets stuffed with the words of Baldwin, hands grasping rage and love, he takes you with him, along a tightrope hovering above the racial hatred, unnecessary deaths, the ongoing narrative of which Trump is not an exception merely an example. After traversing such a desolate landscape, it’s a miracle that he has almost made it to the other side with the wounded belief that “we will risk everything, finally, to become a truly multiracial democracy.” Glaude framed Baldwin’s words so articulately, so beautifully, so insightfully that he drove me to my own meeting. Raoul Peck has used Baldwin’s essays to narrate his 2016 documentary, I Am Not Your Negro, (Curzon Home Cinema), with the idea and words from Remember This House, a book on Martin Luther King, Malcom X and Medgar Evers, that Baldwin never finished. Peck, using rich, rousing, and harrowing archival material, weaves a story that stitches the civil rights movement to present day America. Baldwin emerges as poet: poet of pain, poet of fury, poet of hope. Hopes though are easily dashed. Fortunately, as Baldwin and Guade embody, hope, crushed, mangled, scarred, can be nursed back to health and stand once more, hopeful. For many, as Joe Biden, having got the poetry out of the way at his inauguration, sat down in the Oval Office, hope seemed to be crawling back into the light. This week Joe, springing from his Peloton, dimmed the switch. Powerful words - aired on The Daily (The New York Times' podcast) - poured from Biden’s mouth when he was seeking the Democratic Party nomination, none more so than those used to describe the current Saudi regime as having “no redeeming social value.” No poet Joe. But someone, maybe even Mohammed bin Salman, known universally as MBS (not much of the lyrical in abbreviations, though it does bring to mind, mine at least, major bowel syndrome), would have some consequences to face for the premeditated and violent murder of an American resident. Sadly, politics and justice are uncomfortable bedfellows and this week Joe bottled it. The geo-political interests of his nation swept any remains, any hope of redress, under the White House rug. MBS has been blowing a lot of hot air westwards but, as scathingly shown in Bryan Fogel’s new documentary The Dissident (Glasgow Film Festival 2021), the concocted breeze of modernisation cannot hide the bloody hands of a repressive regime. The Crown Prince knows the importance of words, so much so that he has spawned a grist of ‘flies’ to spew pro-regime messages on Twitter, covering any critical voice in a coating of MBS sludge. If you want to separate yourself from your phone watch the sinister sequence on what others might be doing with it whilst it's in your hand's grip. The late Palestinian poet Samih Al-Qasim, also knew the power of words, he was imprisoned for his. He despaired, in an interview with the Yemeni writer Abdullah al- Udhari, “it is really unbearable to live under a regime which is afraid of a poem”. I first came across his chilling poem, Slit Lips, in a book, They Shoot Writers, Don't They?, assembled by Index on Censorship’s then editor George Theiner, in 1984: Slit Lips I would have liked to tell you The story of the nightingale that died I would have liked to tell you The story… Had they not slit my lips Samih Al-Qasim Hope rises and falls. Some forty years later Al Qasim’s words echoed in the fictions of Syrian writer Osama Alomar's collection Fullblood Arabian. I read about the work of this remarkable practitioner of the Arabical-qisa al-qasira jiddan, the “very short story ” when reading Lydia Davis’s book of Essays, a boon for any writer looking for guidance and inspiration. His When Tongues Were Cut Off reached back a generation to clasp the pen-wielding hand of Al Qasim. When Tongues Were Cut Off The dictator flew into a rage at his people’s incessant call for democracy. When he asked where democracy could be found they only hung their heads in silence. Finally, he was so fed up that he cut out their tongues to weave a carpet out of them. He was convinced that democracy could only be found in their furrows. As he walked proudly on the carpet woven out of severed tongues, he spoke to his people saying, “I have finally brought you democracy. See how beautiful it is!” No one protested. Osama Alomar Speaking in Tongues (Rachel Clare) I do not live in a dictatorship yet. I do not fear arrest for anything that I write. Neither of these mean that I do not have to choose my words carefully. Or, that those words might not be twisted. Hope rises with freedom of expression. Artists, writers, journalists must be allowed to speak, whether they are agreed with or not. As writers all we have are words. These are mine in memory of a man who only used them. Words that were powerful enough to have a “kill team” sent from his own country to suffocate him, then hack his body into parts with a bone-saw in a consulate in Istanbul. As Jamal Khashoggi’s friend and fellow dissident, Omar Abdulaziz, says in Fogel’s film, “Your voice matters. Your words are important. I learned that from Jamal. He does not have a weapon. He’s just using his words.” If you follow the silk road For J.K. If you follow the silk road don’t look down or back or, to your side keep your eyes straight ahead or better still, close your eyes and let the idea, the silk road enter through your feet Do not stop to look at the woman outside that building into which her fiancé has entered disappearing between the potted saplings flanking the entrance beyond the steel maze of safety threaded with bold blue words Polis Polis Polis cartoon colouring to shade the minotaur she waits, patiently at first, before the excitement is drained and love and hope are dismembered a dream of future things hacked into little pieces the bone of marriage broken she waits outside there still unseen by the men passing her attentive only to their suitcases and the business of the world keeping the silk road smooth covering the stains with more flowing silk Simon Parker

6 Comments

|

Writing into the dark Read More...

May 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly