|

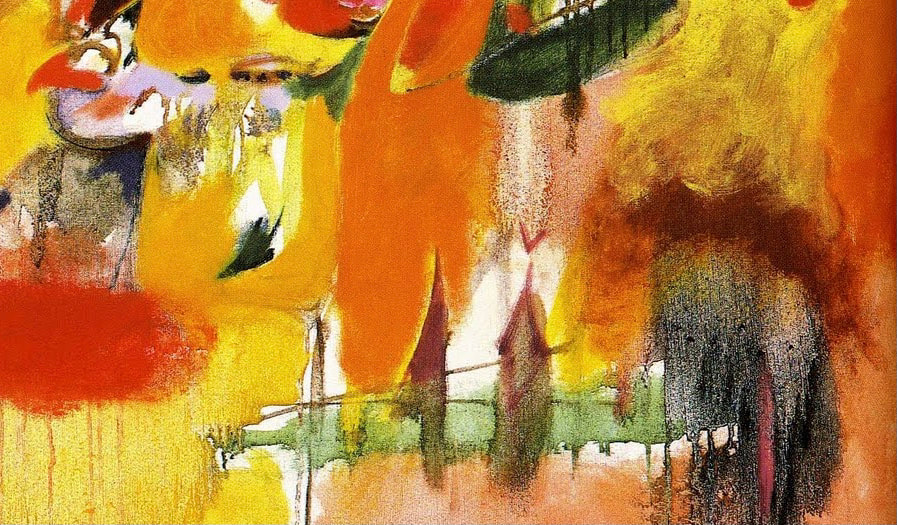

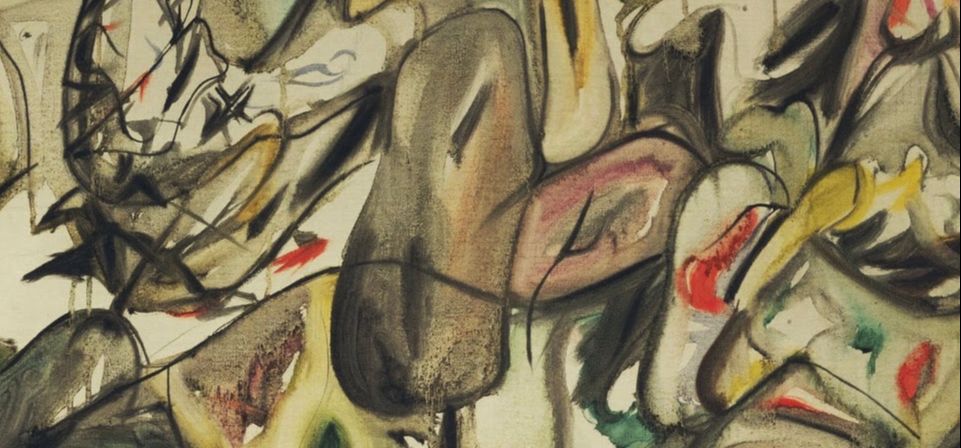

Detail from Water of the Flowery Mill - Arshile Gorky (1944) For a writer the one thing you must do is write. Reading is vital, thinking beneficial, but where the craft is honed, and where your unique and particular voice takes shape, is in the writing. Stendhal, who scratched at the skin of realism in an age of romanticism, advocated a minimum of “twenty lines a day, genius or not.” Harry Matthews, one of the few Americans to be a member of the OULIPO group (writers and mathematicians who looked for new literary forms, game playing and all), took him at his word. Stendhal’s call to action was an attempt to finish the book he was working on. Matthews “deliberately mistook his words as a method for overcoming the anxiety of the blank page” and ended up producing a fascinating book, 20 Lines a Day, with reflections on writing, raking leaves, phone calls, friendship and much more. Since 2017, the twenty line dictum has driven my writing through the first coffee. This twenty line sprint is one of many ways to get the writing day started. Throughout lockdown, alongside playing a daily writing game exploring form, I combined my desire to write about visual art with this daily sprint. What follows takes off from a line of Arshile Gorky's which I came across in the brilliant biography of this troubled artist, Black Angel by Nouritza Matossian. Gorky, who had escaped the Armenian genocide in 1915, died alone when the weight of circumstance finally overwhelmed him. His work lives on and so does his legacy which shaped American painting from the 1940s onwards. Detail from The Leaf of an Arichoke is an Owl - Arshile Gorky (1944) "One artist could bang his hands against the table and years, even centuries later, another could feel the rhythm." - Arshile Gorky One artist could bang his hands against the table and years, even centuries later, another could feel the rhythm; pulsings, gentle or violent, rippling through a new work, riffing on the driving beat of former melodies to make new meaning. Searching for a voice amidst the vocal outpourings of a lustier or loftier throat calling, follow me, and follow me, until you can find your own path. My footsteps will be tip-tapping in your ear but you will be dancing to your own tune. Drunk with a desire to make you stand upon the table, let that rhythm penetrate your soles. Climbing through shin and groin, your flesh will move to a newborn beat. Beating down the shrill voice that screams all endeavour is meaningless, you will dance, tap out your tune, regardless of whether others will take your hand, your lead, or any notice of you at all. Dance with your body, your body, your life, your heart. Your head left looking backwards as you shimmy into an oiled sunset. The sun also sets you know Hemingway. Its day spent in a descending rhythm that drops into darkness. An empty dance floor that has no light. You can dance in the black of night. A nighttime rhyme of black blackening, blackness. Dressed for death but too much to do before the bony hand leads you away. Life lends you its drumsticks, beat out that tempo, shred skin with your pounding, A pounding that has stolen money from the masters. They wont mind, being dead, but a small breath may touch their cold lips, kissing farewell in the earth’s loam. Thank you. I will dance until I die. One eye kept on you, my still and silent friend. You do not hear it but it will carry me across the dance floor, the maple, the canvas, the country and the strains of this senseless life. I will dance until there is nowhere left to dance on. Your rhythm is ceaseless, like a wave that cannot find a shore. A surefire sound that syncopates the pulse, echoes in my strut, and smothers the canvass’s cries for help. Do not let the paint dry, do not let the stroke end. The end is the edge of existence and paint cannot adhere to nothingness. Dance and drip, smudge, smear and stroke this feeble brain into action, an answer: When will the rhythm fade?

7 Comments

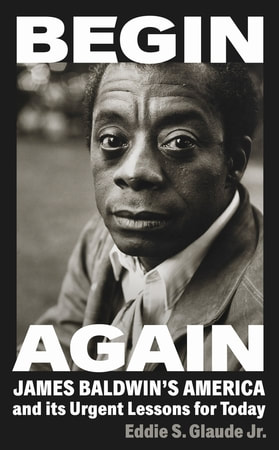

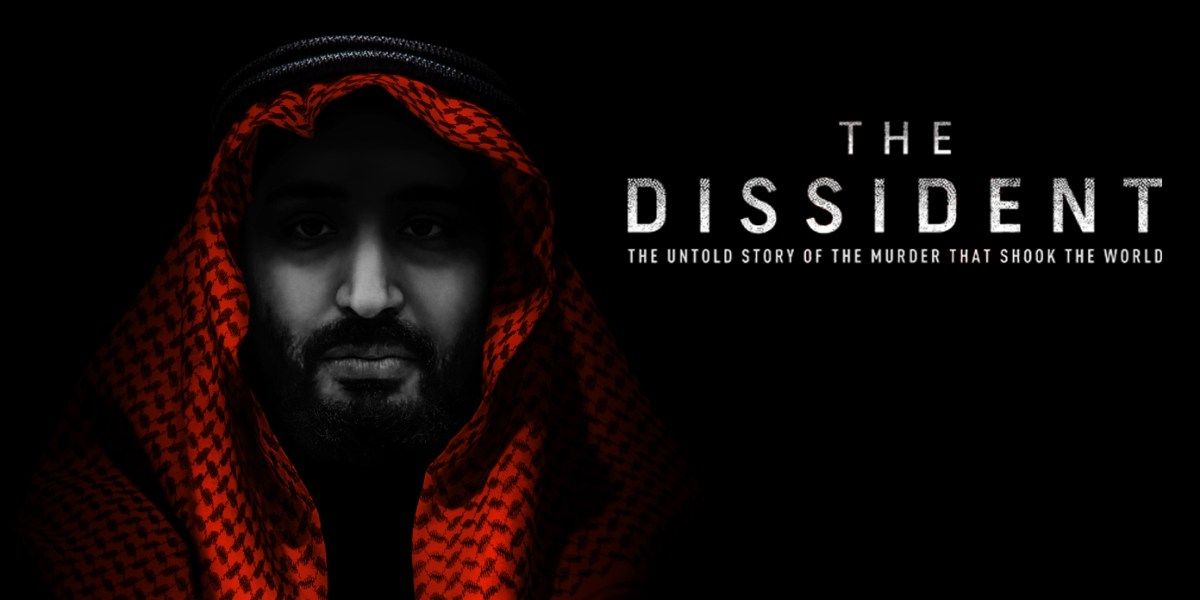

Eye-book (Rachel Clare) “Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.” Ursula K. Le Guin Words matter. The words we choose - we do have a choice - to use and the way that we organise them says so much about who we are, who we want to be and our hopes for the world that we live in. Writers - journalists and artists - work with words, they know that words matter. Politicians use a lot of words but rarely are they handled as precious materials. Words that may have been used in rhetorical flourishes to garner votes are forgotten, redacted, or hoist into shiny new configurations to ‘clarify’ what was really meant. This week the power of words, their consequences and their failings, have been strung out before me as I’ve stumbled from Baldwin to Biden to Khashoggi Last weekend, I took a walk through the recently published Begin Again with Eddie S. Glaude JR, who takes James Baldwin as poet guide to find his way to hope amidst the rubble of American democracy and race relations. This wonderful exploration of the failings of the United States and beyond sees Glaude navigate a troubled America: an America that repeats itself, an America that seems incapable of learning, an America that has been stolen. His pockets stuffed with the words of Baldwin, hands grasping rage and love, he takes you with him, along a tightrope hovering above the racial hatred, unnecessary deaths, the ongoing narrative of which Trump is not an exception merely an example. After traversing such a desolate landscape, it’s a miracle that he has almost made it to the other side with the wounded belief that “we will risk everything, finally, to become a truly multiracial democracy.” Glaude framed Baldwin’s words so articulately, so beautifully, so insightfully that he drove me to my own meeting. Raoul Peck has used Baldwin’s essays to narrate his 2016 documentary, I Am Not Your Negro, (Curzon Home Cinema), with the idea and words from Remember This House, a book on Martin Luther King, Malcom X and Medgar Evers, that Baldwin never finished. Peck, using rich, rousing, and harrowing archival material, weaves a story that stitches the civil rights movement to present day America. Baldwin emerges as poet: poet of pain, poet of fury, poet of hope. Hopes though are easily dashed. Fortunately, as Baldwin and Guade embody, hope, crushed, mangled, scarred, can be nursed back to health and stand once more, hopeful. For many, as Joe Biden, having got the poetry out of the way at his inauguration, sat down in the Oval Office, hope seemed to be crawling back into the light. This week Joe, springing from his Peloton, dimmed the switch. Powerful words - aired on The Daily (The New York Times' podcast) - poured from Biden’s mouth when he was seeking the Democratic Party nomination, none more so than those used to describe the current Saudi regime as having “no redeeming social value.” No poet Joe. But someone, maybe even Mohammed bin Salman, known universally as MBS (not much of the lyrical in abbreviations, though it does bring to mind, mine at least, major bowel syndrome), would have some consequences to face for the premeditated and violent murder of an American resident. Sadly, politics and justice are uncomfortable bedfellows and this week Joe bottled it. The geo-political interests of his nation swept any remains, any hope of redress, under the White House rug. MBS has been blowing a lot of hot air westwards but, as scathingly shown in Bryan Fogel’s new documentary The Dissident (Glasgow Film Festival 2021), the concocted breeze of modernisation cannot hide the bloody hands of a repressive regime. The Crown Prince knows the importance of words, so much so that he has spawned a grist of ‘flies’ to spew pro-regime messages on Twitter, covering any critical voice in a coating of MBS sludge. If you want to separate yourself from your phone watch the sinister sequence on what others might be doing with it whilst it's in your hand's grip. The late Palestinian poet Samih Al-Qasim, also knew the power of words, he was imprisoned for his. He despaired, in an interview with the Yemeni writer Abdullah al- Udhari, “it is really unbearable to live under a regime which is afraid of a poem”. I first came across his chilling poem, Slit Lips, in a book, They Shoot Writers, Don't They?, assembled by Index on Censorship’s then editor George Theiner, in 1984: Slit Lips I would have liked to tell you The story of the nightingale that died I would have liked to tell you The story… Had they not slit my lips Samih Al-Qasim Hope rises and falls. Some forty years later Al Qasim’s words echoed in the fictions of Syrian writer Osama Alomar's collection Fullblood Arabian. I read about the work of this remarkable practitioner of the Arabical-qisa al-qasira jiddan, the “very short story ” when reading Lydia Davis’s book of Essays, a boon for any writer looking for guidance and inspiration. His When Tongues Were Cut Off reached back a generation to clasp the pen-wielding hand of Al Qasim. When Tongues Were Cut Off The dictator flew into a rage at his people’s incessant call for democracy. When he asked where democracy could be found they only hung their heads in silence. Finally, he was so fed up that he cut out their tongues to weave a carpet out of them. He was convinced that democracy could only be found in their furrows. As he walked proudly on the carpet woven out of severed tongues, he spoke to his people saying, “I have finally brought you democracy. See how beautiful it is!” No one protested. Osama Alomar Speaking in Tongues (Rachel Clare) I do not live in a dictatorship yet. I do not fear arrest for anything that I write. Neither of these mean that I do not have to choose my words carefully. Or, that those words might not be twisted. Hope rises with freedom of expression. Artists, writers, journalists must be allowed to speak, whether they are agreed with or not. As writers all we have are words. These are mine in memory of a man who only used them. Words that were powerful enough to have a “kill team” sent from his own country to suffocate him, then hack his body into parts with a bone-saw in a consulate in Istanbul. As Jamal Khashoggi’s friend and fellow dissident, Omar Abdulaziz, says in Fogel’s film, “Your voice matters. Your words are important. I learned that from Jamal. He does not have a weapon. He’s just using his words.” If you follow the silk road For J.K. If you follow the silk road don’t look down or back or, to your side keep your eyes straight ahead or better still, close your eyes and let the idea, the silk road enter through your feet Do not stop to look at the woman outside that building into which her fiancé has entered disappearing between the potted saplings flanking the entrance beyond the steel maze of safety threaded with bold blue words Polis Polis Polis cartoon colouring to shade the minotaur she waits, patiently at first, before the excitement is drained and love and hope are dismembered a dream of future things hacked into little pieces the bone of marriage broken she waits outside there still unseen by the men passing her attentive only to their suitcases and the business of the world keeping the silk road smooth covering the stains with more flowing silk Simon Parker So, a sprint into foolishness... Having just finished George Saunders' wonderful new book (A Swim In a Pond In The Rain) on reading and writing, in which he repeatedly extols the importance of spending time with, and on, the re-write; and, being a long time admirer of Donald Hall's poignant late essays (Essays After Eighty & Carnival Of Losses) where he reveals that he sometimes changes a word between sixty and three hundred times, I am ignoring their advice: Letting something sail into the world because of the wind behind it, rather than a scrupulous and methodical check on whether it is a sea worthy vessel. Late last night, as an unexpected snowfall entered its final melting, I sat reading Luke Mogelson's troubling and telling essay The Storm (Among the Insurrectionists) in this week's New Yorker. This followed: In Him We Trust God must be sleeping or have died a while back, 'otherwise, ' she said 'he would have smite those motherfuckers' whose twisted mouths conspire to set fire to truth with their firsting dragon breath, their tattooed hands hurling history onto the pyre of stories that cause indigestion or inconvenience a roadblock on the pursuit to happiness "Stop the steal, beat the seal, to death we don’t like the colour of his pelt and how the hell did he sign the ballot paper anyway Af- af- af- af- af- af- after this we are the flippers. Stop the clocks, the count this is the end of the world as we know it" Lady Justice has her blindfold ripped from her face, her lips painted blue so that she can sing a proud boy’s anthem extinguished dreams have fallen from the mountain and there he is, god, sliding gleefully down its side having abandoned his angels to march with them Groyper, they call, slapping his stooped back and his big old white feet goose along with them to whose house? "Our House!" The fountain has poured its black liquid for so long that words are forming in its raging foam, parasite, parasitism gurgles and spills over its stoney lip, staining their green and pleasant land "Look what it’s done to our lawn, ma" Somewhere on the floor of a deserted building a shape with coyote fur, buffalo horns and the body of a man his wounded animal wrath seethes through megaphone “I will be he’rd. We will be he’rd.” He turns his woolly head in thanks to their heavenly father, slumped against a lectern slack jawed, breath wheezing from gaping mouth and a yellow plastic shard embedded in his cheek “We need more firepower” he barks © Simon Parker  The Elephant in the Room (Simon Parker)  What we talk about when we talk about death... Death usually ushers us out of the world but with me he started early, accompanying me into it. He will, of course, be beckoning me at the end, pulling me slowly and painfully, or hurling me into darkness, but he is so familiar that I won’t be scrabbling to get away. I was born dead, unable to breathe, and put on a ventilator. Eight and half minutes later, medical intervention had given my lungs enough of a rehearsal that I was able to start taking on the job myself. I have always, sometimes jokingly, sometimes as explanation, offered this episode as the beginning that led me to become death’s familiar. I have always thought about death, read about it, pictured my own dying, and I continue to read and write about how we die, and what it might mean for living. The daily death toll that has dominated the media landscape has thrown this shadowy figure centre stage, a blazing spotlight revealing what was always there but carefully hidden away. The gruesome fascination with counting how many have died in tragedies around the world often seals away, like a trees protective healing after a leaf has dropped, any intimate letting in of death. Covid 19 with its rapacious scything and its blazoning across the news has broken the seal. The leaves of trees have suffered heat stress. As we moved through the twentieth century and set out into the 21st, death has been shepherded away from the public eye. As Atul Gawande notes, in his beautifully humane book, Being Mortal, in the 1940s over eighty percent of people died at home, by the 1980s just seventeen percent did. Coronavirus may not have returned dying to the domestic setting, but it has brought death’s shadow to all of our doors. In a Position Paper published in The Lancet , Psychiatry, one of the authors, Prof Rory O’Connor, writes, ”Increased social isolation, loneliness, health anxiety, stress and an economic downturn are a perfect storm to harm people's mental health and wellbeing,”. This distressing and damaging consequence has wreaked havoc on people’s lives and torn at the already frayed seams of the mental health infrastructure. What hasn’t been included in the assessment though, is the clarion call of mortality. How the brazen, public appearance of death, has drawn our gaze. We live in sanitised times. We deny death’s dominion. But as political philosopher John Gray argues in Straw Dogs, his corruscating critique of American styled liberalism, despite the veneer and polish of civilisation we are still “animals” over which death will always have dominion. What we have become masters of, especially with the elevating of the individual as product, is tidying death away. With the current pandemic the mess keeps spilling back out. Scrabbling towards the end (Simon Parker) Back in 2015, as my father lay on his death bed at my sister’s home, I tried to talk to him about dying. I hoped that by talking he may feel less alone, that by sharing some of the fears and anxieties, the thoughts and feelings circling in his head, he would go gently into “the dying of the light”. He, as he had always done in my lifetime, wouldn’t communicate and the subject was only approached through humour. Humour had protected him in life, and it would serve him in death. What I felt, more about his life than his death, was that that humour, an understandable reflex against the pain of the past, stopped him living. Mark Twain argued that The fear of death follows from the fear of life. A man who lives fully is prepared to die at any time. The last thing my father said was a joke. He pretended that the nurse who was putting a needle into his arm for morphine had hurt him. Something along the lines of, It’s not enough that I’m dying, you want to beat me up as well. When the undertakers arrived to take his body away, they slid the pillow from beneath his head which stayed exactly where it was. I marvelled at this empty space, this vacuum between his neck and head and the mattress. He was gone. Death, its rigour, held this gravity defying place. There was nothing that we had said to each other to fill it. Reading and writing are a way of life, not, as some would argue, a retreat from it. I wrote about my father’s dying, and I spent the months after reading books about death and how we approach our end. This wasn’t running away from the grief but a way of wandering through it. I read, I cried, I thought, I questioned. I wrote a play, Aching Parts, about how we die. Most days I think about death, about dying, not in a morose and fearful way but instinctively. Now, death is everywhere and everyone is thinking about it. Or are they? There is a scramble to return to things as they were. For schools to reopen, for people to return to work, to the gym, for people to escape the isolation and strangeness that the pandemic has brought, for death to be tidied away once again. This feels like a missed opportunity. Economic worry, which carries education in its wake, is fuelling ideas about the future. With death having come so close to all of us, with our mortality so baldly exposed, is this what we want for the one short life we live. Death awaits so why don’t we start living as we really want to. Aren’t these the conversations, the desires, that should be driving us beyond an unchanged return. Pushing us to the life worth living, its energy increased by an acceptance of the inescapable end. Death should be kept from its hiding place. The tireless and brilliant Maria Popova has shown how other countries sensitively place death centre stage in children’s books, starting the conversation early, with death a protagonist in many wonderful tales. These stories characterise, and normalise, death for young children, and, I believe, make their lives much richer for it. Two of the books that Popova introduced me to, I use when teaching both adults and children, and often, in the many conversations I have about death. In Wolf Erlbruck’s Duck, Death and Tulip and Glenn Ringtved’s and illustrator Charlotte Pardi’s, Cry Heart But Never Break, there is an uplifting tenderness and truth about how it all ends. Erlbruck’s Duck, who has failed to noticed that Death has been following her all of her life, suddenly realises he is there. They spend time together, becoming friends. Duck suggests they go to the pond but the water proves too cold for Death, and Duck has to keep him warm throughout the night, her neck and wing laying across his sleeping body. Death is moved as nobody had ever offered such intimacies. This heartbreaking moment of communion and togetherness cannot prevent Death from doing his job. Ringtved and Pardi, delicately tread the same path. Death has come to a house to collect an elderly woman who is sick. So that he doesn’t frighten her grandchildren he leaves his scythe outside, resting it gently next to the front door. The children, to prevent Death going upstairs to their grandmother, keep pouring him tea and telling him stories. When Death can take no more tea, he tells these anxious children a story of his own, a story that strikes the same bell in Keats’ “temple of Delight” where “Veil'd Melancholy has her sovran shrine”. After listening, the children relent, accepting that you cannot have life without death. They let their grandmother go. Inevitably, we must follow out grandmothers and grandfathers, our fathers and mothers, but don’t we want to follow them knowing we have lived a life without fear. Until death is part of the conversation that may never happen. Erlbruck’s Duck and Death

|

Writing into the dark Read More...

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly